575.01/62 QH361.G66 1980 Preceded by Followed by The Panda's Thumb: More Reflections in Natural History (1980) is a collection of 31 essays by the. It is the second volume culled from his 27-year monthly column 'This View of Life' in magazine. Recurring themes of the essays are evolution and its teaching, science biography, probabilities and common sense. The title essay (of 1978, originally titled 'The panda's peculiar thumb') presents the paradox that poor design is a better argument for evolution than good design, as illustrated by the of the 's 'thumb'—which is not a thumb at all—but an extension of the radial. Topics addressed in other essays include the female brain, the hoax,, and the relationship between dinosaurs and birds. The Panda's Thumb won the 1981 U.S..

With sales of well over one million copies in North America alone, the commercial success of Gould's books now matches their critical acclaim. The Panda's Thumb will introduce a new generation of readers to this unique writer, who has taken the art of the scientific essay to new heights. Were dinosaurs really dumber than lizards? Why, after all, are roughly the same number With sales of well over one million copies in North America alone, the commercial success of Gould's books now matches their critical acclaim. The Panda's Thumb will introduce a new generation of readers to this unique writer, who has taken the art of the scientific essay to new heights. Were dinosaurs really dumber than lizards? Why, after all, are roughly the same number of men and women born into the world?

What led the famous Dr. Down to his theory of mongolism, and its racist residue? What do the panda's magical 'thumb' and the sea turtle's perilous migration tell us about imperfections that prove the evolutionary rule? The wonders and mysteries of evolutionary biology are elegantly explored in these and other essays by the celebrated natural history writer Stephen Jay Gould. Having recently settled in Australia I found the information on Marsupials in South America highly interesting.

Stephen Jay Gould: An. Wallace, in The Panda's Thumb. Stephen Jay Gould (1941-2002. Bully for Brontosaurus. Stephen Jay Gould has a wide range of interests. Stephen Jay Gould Panda Thumb Pdf Writer. Jim Collins - Tools - Discussion Guide. For a selection of just the very best of Jim's list, read here.

I also enjoyed his somewhat internal debates about dinosaurs. I still haven't latched on to his writing as much as I would have liked.

The content is really good and he has a great sum up near the end about a lot of 'points' other science writers have made that really comes through with some fervor about the way that bats and bees see and what the world is to us. The sexual and racial Having recently settled in Australia I found the information on Marsupials in South America highly interesting. I also enjoyed his somewhat internal debates about dinosaurs. I still haven't latched on to his writing as much as I would have liked. The content is really good and he has a great sum up near the end about a lot of 'points' other science writers have made that really comes through with some fervor about the way that bats and bees see and what the world is to us. The sexual and racial issues surrounding Evolution in scientific history is a subject I detest but he still was able to keep me interested during that portion as well. Its not a book I would re read but it was a good once over.

This was a hugely enjoyable book by an extremely talented writer. The thought most running across my mind when I was reading this book was: 'Where can I get more Stephen Jay Gould books?!' Since it is a collection of essays, I don't really want to review any of them personally. Sure, some of the science here is 30 years old (Gould was always sharp on the uptake though), some of it is out of favour (say Gould's ideas on the gene-centric view of evolution), but you'll still enjoy reading every bit This was a hugely enjoyable book by an extremely talented writer. The thought most running across my mind when I was reading this book was: 'Where can I get more Stephen Jay Gould books?!' Since it is a collection of essays, I don't really want to review any of them personally. Sure, some of the science here is 30 years old (Gould was always sharp on the uptake though), some of it is out of favour (say Gould's ideas on the gene-centric view of evolution), but you'll still enjoy reading every bit of it.

There are ideas about the evolution of dinosaurs, magnetic bacteria, South American marsupials and even Mickey Mouse. Themes such as racism and sexism, as ever, continue to play a major role in his examination of the past.

What was most enjoyable was the fact that Gould is such a sympathetic writer, yet his work is full of wit and consideration. The Panda's Thumb made for an excellent book to pick up, regardless of what I was doing or what my mood was and immediately get lost in whatever world Stephen Jay Gould transported you to.

This wonderful book is a collection of 31 short articles that appeared in the magazine 'Natural History' in the late 1970's ('77-'79).each 'chapter' is an independent read (for the most part) that, if you are a patient pooper, can be finished in a single seating. The topics range from discussions about Darwin's 'Origin of Species' to Agassiz unenlightened racism to the length of a year 500 million years ago to Mickey Mouse's head size.

Gould is a great writer with full command of natural histo This wonderful book is a collection of 31 short articles that appeared in the magazine 'Natural History' in the late 1970's ('77-'79).each 'chapter' is an independent read (for the most part) that, if you are a patient pooper, can be finished in a single seating. The topics range from discussions about Darwin's 'Origin of Species' to Agassiz unenlightened racism to the length of a year 500 million years ago to Mickey Mouse's head size. Gould is a great writer with full command of natural history and a knack in making a difficult subject both informative and entertaining.

The only reason that I 'dinged' the rating is that some of the articles.those involving paleontology and general geology.are very much dated and out of step with the current thinking of earth's history. I know that that is somewhat unfair, but, hey, this review is intended for those potential readers who might assume that the science presented represents the cutting edge some aspects of the earth sciences. There have been huge advances in both discoveries (e.g. Feathered dinosaurs) and evolutionary philosophy.there is no way SJG could have predicted all of that. The book is highly entertaining.I recommend it! The greatest modern voice for the neo-Darwinian synthesis. He and a colleague, whose name I forget, re-purposed Kipling's term 'just-so stories' to describe evolutionarily plausible but unprovable explanations for things.

An amazing critical thinker, Gould realized that if you didn't establish some way of critiquing evolutionary explanations, they would become the equivalent of folk explanations, overpredicting to the point that they could never be disproven. Once evolutionary explanations becam The greatest modern voice for the neo-Darwinian synthesis.

He and a colleague, whose name I forget, re-purposed Kipling's term 'just-so stories' to describe evolutionarily plausible but unprovable explanations for things. An amazing critical thinker, Gould realized that if you didn't establish some way of critiquing evolutionary explanations, they would become the equivalent of folk explanations, overpredicting to the point that they could never be disproven.

Once evolutionary explanations became non-disprovable, it stops being a science and starts being a belief, like believing in god. So he spent a lifetime not just doing his own research but in popularizing disciplined neo-Darwinian critical thinking in this series of essays in Natural History magazine or Nature magazine, I forget. Most of my understanding of the neo-Darwinian synthesis comes from reading Gould.

'An early collection of Stephen Jay Gould's essays from his column in Natural History magazine, The Panda's Thumb was an enjoyable read, assuming you like natural history. It's the third of Gould's collections I've read, and the earliest I've read as well, but it held up well over time. Composed in the late '70s -- '78 and '79, I believe -- the essays in The Panda's Thumb bear the mark of Gould's charming, articulate style.' Read the rest of my review at [ 'An early collection of Stephen Jay Gould's essays from his column in Natural History magazine, The Panda's Thumb was an enjoyable read, assuming you like natural history. It's the third of Gould's collections I've read, and the earliest I've read as well, but it held up well over time.

Composed in the late '70s -- '78 and '79, I believe -- the essays in The Panda's Thumb bear the mark of Gould's charming, articulate style.' Read the rest of my review at []. Stephen Gould has a remarkable ability to cover scientific concepts in an accessible manor without dumbing things down. The format of his 'Reflections.'

Produces bite-sized meditations on evolution and natural history topics. My only concern is with the constant movement of science, that insights of the seventies may be stale in the current thinking. I wonder at times if I am reading a time capsule of a particular mode of thought, or the dawn of the accepted way of thinking.

Things I thought we Stephen Gould has a remarkable ability to cover scientific concepts in an accessible manor without dumbing things down. The format of his 'Reflections.' Produces bite-sized meditations on evolution and natural history topics. My only concern is with the constant movement of science, that insights of the seventies may be stale in the current thinking. I wonder at times if I am reading a time capsule of a particular mode of thought, or the dawn of the accepted way of thinking.

Things I thought were interesting: 1) The terms Idiot, Moron, and Mongoloid once had Scientific Relevance. Gould had to write an essay advocating the use of Downs' Syndrome over the still accepted Mongoloid Idiot. 2) The idea that Birds should be reclassified under a Family of Dinosaurs captures my imagination. Since it's been forty years, I wonder where that ended up. 3) Finally, the way Gould captures the impact of size as an environment for adaptation breaks up most of the science fiction tropes of big vs. Little ('The Fly,' 'The Fantastic Voyage') while opening whole new doors in understanding of nature.

The Panda's Thumb is an overall interesting book dealing with the curiosities of evolution through a compendium of articles written by Gould mostly in the 70s for Nature magazine. The 1992 edition even goes over some clarifications which have come into light in the two decades since the articles have been published. I think the book is a fairly readable popular natural sciences book, although the fragmentation that comes from it being an anthology of articles does make it seem aimless at times. The Panda's Thumb is an overall interesting book dealing with the curiosities of evolution through a compendium of articles written by Gould mostly in the 70s for Nature magazine. The 1992 edition even goes over some clarifications which have come into light in the two decades since the articles have been published.

I think the book is a fairly readable popular natural sciences book, although the fragmentation that comes from it being an anthology of articles does make it seem aimless at times. I think the genre has advanced in terms of content and readability by leaps and bounds in the last two decades and while Gould is still a good read, I do believe there are lots of equally good books available which have a bit more structure than the Panda's Thumb. As for anthologies I am a big fan of The Best American Science and Nature Writing yearly series.

This is a book of essays originally published by Gould in Natural History magazine, during the time that he was its editor (one of several such books, in fact). As such, it is an effort on his part to appeal to an educated popular audience with snippets of information about current research, particularly into paleontology and evolutionary science (his specialties), but also into other areas of biology and even geology and related sciences. Often, he is responding to then-current media fads, by t This is a book of essays originally published by Gould in Natural History magazine, during the time that he was its editor (one of several such books, in fact).

As such, it is an effort on his part to appeal to an educated popular audience with snippets of information about current research, particularly into paleontology and evolutionary science (his specialties), but also into other areas of biology and even geology and related sciences. Often, he is responding to then-current media fads, by trying to provide corrective information to misrepresentations of science in the popular press. This may partially explain the odd choice of title – the panda’s “thumb” doesn’t seem as sensational a topic to me as dinosaurs’ relationship to birds or the comparative measurements of male and female (human) brains, but perhaps it was the headline-grabber in 1980, for whatever reason. The essays are grouped into eight categories, explained nicely in a very well-written introduction, but without a final conclusion to tie them all together into any kind of grand theory. This leaves the book feeling a bit disjointed, and uncertain of purpose – Gould seems to have a point in each essay and even each section, but not really a “big idea” for putting them together in one volume. It is therefore best approached as a kind of exercise for the brain, and not a serious undertaking to comprehend evolutionary science. It is well-written and easy enough to follow that science teachers might be able to select single essays to demonstrate points to students, and Gould is amusing enough that students would find him readable.

I’m a pretty good audience for this sort of book, because I don’t know that much about the specialized area Gould works in, but I’m smart enough to keep up with him and nerdy enough to be entertained by stories about science. I was especially interested in some of his historical essays, especially those that demonstrate that discarded theories were not results of irrationality or bad procedure on the part of their originators, but rather changes in overall paradigm.

Gould is very good at demonstrating the social and cultural biases that have stunted scientific inquiry, and draws lessons from past mistakes that can be applied to more recent science. Being unfamiliar with the field and with Gould in particular, I was a bit surprised at how “traditionally” Darwinian he appears to be in these essays. My impression (possibly false) is that over the time since Darwin there have been many newer concepts added to the mix of random mutation and natural selection to explain how life forms develop and change, but Gould seems to be more interested in presenting an unsullied version of Darwin than in complicating that picture. This could have resulted from his concern over the vocal arguments of Creationists (as bad now as they were then), and a desire to keep things simple in a public forum. Or, it may be that evolutionary science was exactly as he presents it in 1980, which is now some time ago.

I was also interested to learn that he strongly disagrees with Richard Dawkins’ argument from The Selfish Gene, also on my reading list, and I will have to remember to come back and check his points when I get around to reading that book. Until I do, I cannot comment on the debate.

Overall, this is a very good book of scientific essays for anyone interested in the subject, and may open up new lines of inquiry to the attentive reader. I bought this second hand over 13 years ago and, after reading it, should not have put it off for so long. The topic of evolution has interest for me for two reasons, the first being that biology is the one core area of science I've not studied formally and the second that it (evolution) has become such a flash-point issue in disputes between science and religion. Written as a series of vignettes about various topics, each was an entertaining and enlightening read, although I'm not sure if I'm a I bought this second hand over 13 years ago and, after reading it, should not have put it off for so long.

The topic of evolution has interest for me for two reasons, the first being that biology is the one core area of science I've not studied formally and the second that it (evolution) has become such a flash-point issue in disputes between science and religion. Written as a series of vignettes about various topics, each was an entertaining and enlightening read, although I'm not sure if I'm any better off in terms of my knowledge about how evolution works. The opening essay concerns the Panda's Thumb, and Gould suggests that in evolution, exceptions rather than norms often prove the rule. However, with each essay comprising an 'exception' (of sorts), I'm not sure that a cohesive picture is drawn as a result. Indeed, I can see how some might take snippets of various essays and use them 'against' evolution. This would be unfortunate, as I think instead we are presented with an area of science that was, and presumably still is, undergoing healthy critical thinking and application.

Many topics are discussed that would have popular appeal. Gould's issue with Dawkin's selfish gene idea is outlined. The evolution of humans, both biological and cultural is considered, with the latter an example of 'Lamarckism' and operating much faster than genetic based changes. Catastrophism and punctuated equilibrium are explored, the latter not suggesting change takes place more or less gradually, but the evidence we have for it in fossils does occur 'rapidly' due to a previously isolated group becoming the dominant and more fossilised species.

Dinosaurs, mickey mouse and the inferiority (or otherwise) of marsupials are also covered. Since Gould was overt in separating the domains of science and religion as mutually exclusive (as I found out recently when reading Sam Harris), the weaving of the Arts, including religious arts infuses his writing, adding to the readability, but offering little in terms of the 'debate' between the two. It certainly makes the read a less confrontational one and those with a religious bent, like myself, will probably find themselves adopting a less defensive stance as they explore what can be a threatening area of science. As far as furthering the discussion between science and religion, I will need to go elsewhere. Around the Year in 52 Books 2017 Reading Challenge.

A book from the middle of your to-be-read list. I am not sure who the target audience for this book is. It is NOT meant for graduate students in biology/evolution since although there is a bibliography, specific sources are not cited within the text. It can't be for the general public since that language alone would be daunting for anyone without a strong background in biology. A series of interesting essays which might be discussed in a one cred Around the Year in 52 Books 2017 Reading Challenge. A book from the middle of your to-be-read list.

I am not sure who the target audience for this book is. It is NOT meant for graduate students in biology/evolution since although there is a bibliography, specific sources are not cited within the text. It can't be for the general public since that language alone would be daunting for anyone without a strong background in biology.

A series of interesting essays which might be discussed in a one credit college class along with some other books important to the history of biology. It is obvious the author is well educated and that he loves and is knowledgeable about music.

What is NOT obvious is whether he is Christian. WHY is this important? Many non-scientists think that you either believe in evolution as fact OR you believe God created everything and that you can not be both a biologist and a Christian. Until the last few chapters I would have sworn Gould is an atheist. After reading the last few chapters I wonder if that is so. I taught biology at 3 different college campuses and the students at one were astounded to learn I am a Catholic. One student eventually did say that I had convinced him plants had evolved, but not animals and certainly not humans.

Of course, at that same school some students were either offended or confused when I referred to humans as animals. I responded that I did not consider myself either a non-nucleated single cell, plant, fungus, nor protest and that left only one option. 1) 'And thus we may pass from the underlying genetic continuity of change---an essential Darwinian postulate---to a potentially episodic alteration in its manifest result---a sequence of complex, adult organisms. Within complex systems, smoothness of input can translate into episodic change in output. Here we encounter a central paradox of our being and of our quest to understand what made us. Without this level of complexity in construction, we could not have evolved the brains to ask such que 1) 'And thus we may pass from the underlying genetic continuity of change---an essential Darwinian postulate---to a potentially episodic alteration in its manifest result---a sequence of complex, adult organisms. Within complex systems, smoothness of input can translate into episodic change in output.

Here we encounter a central paradox of our being and of our quest to understand what made us. Without this level of complexity in construction, we could not have evolved the brains to ask such questions.

With this complexity, we cannot hope to find solutions in the simple answers that our brains like to devise.' ' 2) 'The physical structure of the brain must record intelligence in some way, but gross size and external shape are not likely to capture anything of value.

I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.' ' 3) 'I am, as several other essays emphasize, an advocate of the position that science is not an objective, truth-directed machine, but a quintessentially human activity, affected by passions, hopes, and cultural biases. Cultural traditions of thought strongly influence scientific theories, often directing lines of speculation, especially [.] when virtually no data exist to constrain either imagination or prejudice.' 'The Panda's Thumb' is the second volume in a series of essay collections culled primarily from Gould's column 'This View Of Life' that was published for nearly thirty years in Natural History magazine, the official popular journal of the American Museum of Natural History. Once more readers are treated to elegantly written, insightful pieces on issues ranging from racial attitudes affecting 19th Century science to evolutionary dilemnas such as the origins of the Panda's thumb (Not really a dile 'The Panda's Thumb' is the second volume in a series of essay collections culled primarily from Gould's column 'This View Of Life' that was published for nearly thirty years in Natural History magazine, the official popular journal of the American Museum of Natural History. Once more readers are treated to elegantly written, insightful pieces on issues ranging from racial attitudes affecting 19th Century science to evolutionary dilemnas such as the origins of the Panda's thumb (Not really a dilemna, though 'scientific' creationists might argue otherwise; instead Gould offers an elegant description of how evolution via natural selection works.) and the evolutionary consequences of variations in size and shape among organisms.

Gould is differential to the work of other scientists, carefully considers views contrary to his own, and even points the virtues of the faulty science he criticizes. Those who say contemporary science is dogmatic should reconsider that view after carefully reading this volume or any of the others in Gould's series. Instead, what we see are the thoughts of a fine scientist rendered in splendid, often exquisite, prose. (Reposted from my 2001 Amazon review).

In the introduction, Stephen Jay Gould hastens to remind us once again that he does not consider himself a polymath, merely another tradesman. In the ensuing remainder of the book, only the second collection of his long-running column in Natural History journal, he defies this modest claim by writing on a wide variety of scientific subjects, using an even wider variety of cultural reference points. The Panda's Thumb even has a theme, of sorts, described by Gould as a 'club sandwich' of topics on In the introduction, Stephen Jay Gould hastens to remind us once again that he does not consider himself a polymath, merely another tradesman. In the ensuing remainder of the book, only the second collection of his long-running column in Natural History journal, he defies this modest claim by writing on a wide variety of scientific subjects, using an even wider variety of cultural reference points. The Panda's Thumb even has a theme, of sorts, described by Gould as a 'club sandwich' of topics on biology and history.

A less explicit theme of the book is error and imperfection and their role in science, not just as an unavoidable side-effect of human enterprise but also as its essential driving force. Gould uses his wit to create lessons out of one forgotten and bizarre idea that all rock is actually fossilized microbes, the discredited field of craniometry, and previous generations' misconceptions about the intelligence of dinosaurs, showing us that making mistakes is proof that we are learning. A conglomeration of Gould’s articles and essays about various scientific troubles, anomalies, and paradigm shift resistance specifically aimed at creationist and other anti-science movements, if one can call such things movements. Many times, Gould speaks to the biased human minds that make up the scientific community and the sociological and cultural pressures operating within and upon it. It holds up remarkably well since its publication over 30 years ago. Nr 2003 Full Download more. From Haekel’s insistence on evolutiona a conglomeration of Gould’s articles and essays about various scientific troubles, anomalies, and paradigm shift resistance specifically aimed at creationist and other anti-science movements, if one can call such things movements.

Many times, Gould speaks to the biased human minds that make up the scientific community and the sociological and cultural pressures operating within and upon it. It holds up remarkably well since its publication over 30 years ago.

From Haekel’s insistence on evolutionary recapitulation and Kirkpatrick's insistence that all rocks were made of fossils to Agassiz’s overt racism to the fall of gradualism and dinosaurs’ coldblooded nature, this book is a great panorama of the history of science. The picture it creates is an honest one even if it’s not very pleasant to our egos sometimes.

But that’s what science is all about, i think. I love Stephen Jay Gould. I'd probably love him more if he hadn't died so early. He takes complicated subject matter and writes about it in such a way that it seems like the simplest thing you've ever read. This book is a collection of essays about natural history, just like most of his books are.

This is the first collection of his essays that I've read (I've only read two other books of his, which is absolutely shocking!). There's not really much you can say about his work - it's e I love Stephen Jay Gould. I'd probably love him more if he hadn't died so early. He takes complicated subject matter and writes about it in such a way that it seems like the simplest thing you've ever read. This book is a collection of essays about natural history, just like most of his books are. This is the first collection of his essays that I've read (I've only read two other books of his, which is absolutely shocking!). There's not really much you can say about his work - it's easiest just to say: read it yourself.

Not only does he say everything far better than I ever could, it's totally worth it and you could never regret reading anything he's written (and if you could, then I don't really want to know you). Interesting, and Gould writes well, but flawed. When he talks about Dawkins and the Selfish gene, he is simply wrong, partly I think because he didn't quite understand it, and partly because the idea of selection being on the level of the gene rather than the individual or group offended his sensibilities Later, when he wrote about birds and dinosaurs, he seemed not to fully grasp the full implications of placing the birds in the dinosaur group Thirdly his refutation of gradualism was not just that Interesting, and Gould writes well, but flawed. This book has been sitting on my shelf for a long time, and I'm kicking myself for not reading it sooner.

What a delightful little book of science essays! Each essay is an edited version of his monthly columns at Natural History magazine. Subsequently, the essays are intelligible to the general intelligent reader, but Gould does not thereby sacrifice an appreciation for hard facts and subtle reasoning. Gould makes science come alive with his anecdotes, wry humor, and gentle argumentation about t This book has been sitting on my shelf for a long time, and I'm kicking myself for not reading it sooner. What a delightful little book of science essays!

Each essay is an edited version of his monthly columns at Natural History magazine. Subsequently, the essays are intelligible to the general intelligent reader, but Gould does not thereby sacrifice an appreciation for hard facts and subtle reasoning. Gould makes science come alive with his anecdotes, wry humor, and gentle argumentation about topics ranging from the Panda's thumb to hopeful monsters and everything in between. Nothing is too big or small for Gould to think worthy of an essay. All in all, I highly recommend this book for any student of biology or lover of science. I'm rereading all of Stephen Jay Gould's works.

They are well worth it for pure scientific entertainment. The Panda's Thumb was written in 1980, so it is a bit old. Yet it still stands up well.

The pands has five digits plus a 'thumb' that is not really a thumb at all. It does show how a thumb could form since there is no gene for a thumb. Gould argues against the slow change theory of evolution. Rather he argues for dramatic sudden changes.

I believe Dawkins and others still continue this argum I'm rereading all of Stephen Jay Gould's works. They are well worth it for pure scientific entertainment. The Panda's Thumb was written in 1980, so it is a bit old.

Yet it still stands up well. The pands has five digits plus a 'thumb' that is not really a thumb at all.

It does show how a thumb could form since there is no gene for a thumb. Gould argues against the slow change theory of evolution. Rather he argues for dramatic sudden changes.

I believe Dawkins and others still continue this argument. I was fascinated by the magnetotactic bacterium. They build a magnet in their bodies made of tiny particles. Some of these pieces are a bit dated (not so surprising in a book published in 1980); his rather daring efforts to finger Teilhard de Chardin as a participant in the Piltdown Man hoax were easily refuted by the first researcher to check the documentary evidence.

But his thoughts on punctuated equilibrium are pretty convincing, as is his (less developed here) criticism of Dawkins for obsessing about genes rather than individuals. And his essay on heartbe Some of these pieces are a bit dated (not so surprising in a book published in 1980); his rather daring efforts to finger Teilhard de Chardin as a participant in the Piltdown Man hoax were easily refuted by the first researcher to check the documentary evidence. But his thoughts on punctuated equilibrium are pretty convincing, as is his (less developed here) criticism of Dawkins for obsessing about genes rather than individuals. And his essay on heartbeats and breaths in the lifespan of a mammal was very sobering. A TRUE 'bio-nerd' book.;) I had to read this I think freshman year for a bio class? Road Test Parallel Parking Dimensions Nj.

It was great. Even though I 'had' to read it!) If I remember correctly, each chapter is a separate story/antecdote so its another book, where if you get bored, just skip to the next chapter and you didnt miss a thing! It includes chapters such as: 'Nature's Odd Couples', 'A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse' and, 'Were Dinosaurs Dumb?'

Its all about Natural History/Evolution so you have to at least partially s A TRUE 'bio-nerd' book.;) I had to read this I think freshman year for a bio class? It was great. Even though I 'had' to read it!) If I remember correctly, each chapter is a separate story/antecdote so its another book, where if you get bored, just skip to the next chapter and you didnt miss a thing! It includes chapters such as: 'Nature's Odd Couples', 'A Biological Homage to Mickey Mouse' and, 'Were Dinosaurs Dumb?' Its all about Natural History/Evolution so you have to at least partially subscribe to Darwin's reationale to truly appreaciate.but I read it at my Catholic University if that tells you anything! OK, my favorite part?

Where Gould explains the evolution of Disney's Mickey Mouse and how Mickey seems to be the original 'Benjamin Button' de-aging thru the decades. And Goofy is probably the only real 'adult' in the entire cartoon gang. Poor Goofy, I'd never thought of him as being either a widower or a divorcee or maybe even a single parent before reading this book. By the way, Pandas don't actually have thumbs, they have, ahhhh, but I'll let you go read the book and find out for youselves:-). Gould's second collection of articles from Natural History. Like the first, very interesting and fun to read, if now somewhat dated. I think that in some of the articles, he tries a little too hard to be a 'gadfly' and generalizes his conclusions too much, but he always provokes thought.

I enjoy reading articles on evolutionary theory that don't get bogged down in arguing with creationists, but take the facts for granted and discuss the more interesting questions of How and Why things happened t Gould's second collection of articles from Natural History. Like the first, very interesting and fun to read, if now somewhat dated. I think that in some of the articles, he tries a little too hard to be a 'gadfly' and generalizes his conclusions too much, but he always provokes thought. I enjoy reading articles on evolutionary theory that don't get bogged down in arguing with creationists, but take the facts for granted and discuss the more interesting questions of How and Why things happened the way they did. Mostly interesting if older, outdated essays on evolution. The guy is curious about many things I've never thought to be curious about and covers a lot of ground. Someone actually did a study on the heart rates of spiders?

This is about the only place I'd ever hear about it. The postscripts were nice but the book is so old the postscripts need postscripts. Early on in the book there are a few places where the author let strong feelings for a topic get the best of him and a touch of arrogance sho Mostly interesting if older, outdated essays on evolution. The guy is curious about many things I've never thought to be curious about and covers a lot of ground.

Someone actually did a study on the heart rates of spiders? This is about the only place I'd ever hear about it. The postscripts were nice but the book is so old the postscripts need postscripts.

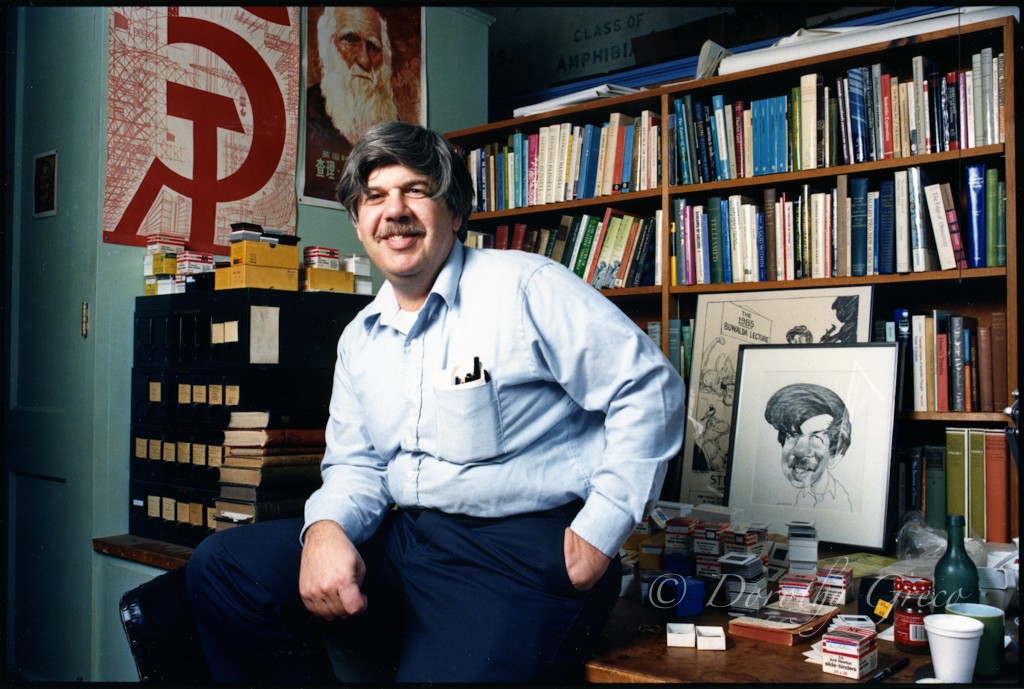

Early on in the book there are a few places where the author let strong feelings for a topic get the best of him and a touch of arrogance shows through, but most of the essays are unaffected. Stephen Jay Gould was a prominent American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science. He was also one of the most influential and widely read writers of popular science of his generation. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Most of Gould's empirical research was on land snails. Gould Stephen Jay Gould was a prominent American paleontologist, evolutionary biologist, and historian of science.

He was also one of the most influential and widely read writers of popular science of his generation. Gould spent most of his career teaching at Harvard University and working at the American Museum of Natural History in New York. Most of Gould's empirical research was on land snails. Gould helped develop the theory of punctuated equilibrium, in which evolutionary stability is marked by instances of rapid change. He contributed to evolutionary developmental biology.

In evolutionary theory, he opposed strict selectionism, sociobiology as applied to humans, and evolutionary psychology. He campaigned against creationism and proposed that science and religion should be considered two compatible, complementary fields, or 'magisteria,' whose authority does not overlap. Many of Gould's essays were reprinted in collected volumes, such as Ever Since Darwin and The Panda's Thumb, while his popular treatises included books such as The Mismeasure of Man, Wonderful Life and Full House.